Bob Arnold

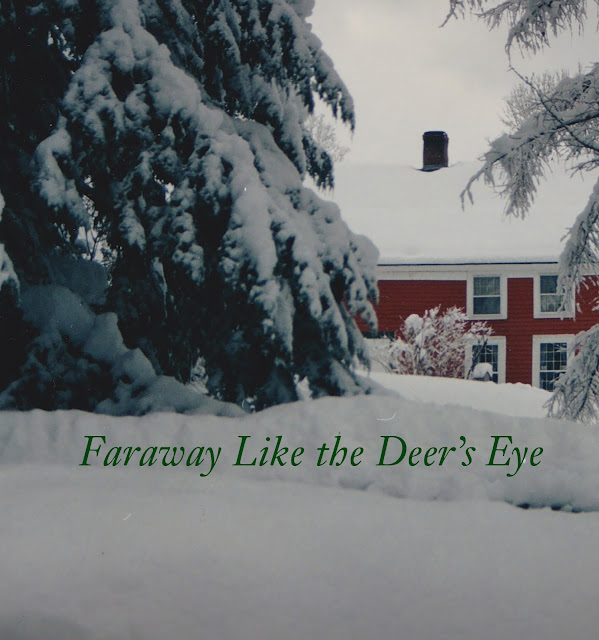

Faraway Like the Deer’s Eye

— A Saga —

FOUR BOOKS IN ONE VOLUME ~

A Poet’s Memoir

50 Years of Longhouse & Poets

A Builder’s Life, with photo assembly

The Selected Poems of Bob Arnold

An afterword by Andrew Schelling

—————

444 pages, text & over 900 images in color

First edition, one of only 100 copies

$50 plus $5 shipping

We accept Paypal

Please use our email address of

longhousepoetry@gmail.com

Payable by check ~

Longhouse

PO Box 2454

West Brattleboro, Vermont 05303

on BOB ARNOLD

The final issue of L=A=N=G-U=A=G=E magazine had come out. If you lived in the Bay Area in the eighties when much rambunctious art was happening, you always got hungry for magazines to bring you the news. It was the era of punk rock and skateboards, the Grateful Dead and Indian raga. People talked about bioregion, Marx, Zen, animal rights, Earth First! It was the era of Ronald Reagan, Turtle Island Press, Oakland A’s baseball, Sun Ra and poetry. Ben Friedlander and I figured we could put out a magazine with the swift insouciant feel of a ‘zine, like L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E had. We could make it by hand though, make it rough, smart, and funny. And give it a name to crack your teeth on: Jimmy & Lucy’s House of “K.”

We wanted to run five short Lorine Niedecker poems. She’d been dead a dozen years and the books had all disappeared. I wrote Cid Corman in Kyoto to get permission. Cid and I started to swap letters, and in an early blue aerogram he told me I should look up a poet somewhere near Brattleboro, Vermont. The name was Bob Arnold.

I have no record of the date Bob and I started to swap letters ourselves. It’s been thirty or forty years. Bob, it turned out, lived with Susan and their son Carson along the Green River, down a rural back road often hard to navigate due to ice or mud. Getting there sounded like the Bashō-type journey I like. “Go through Green River Covered Bridge, take immediate left onto River Road (dirt), follow the Green 1.6 miles to our house. Go past the house to an open barway and turn in.” Oddly, this homestead might be more remote now than it felt in the seventies when Bob settled there. I’d been around the region as a child, figured I’d like to see Shelburne Falls and Marlboro again, and promised I’d visit what they called Longhouse.

Bob began sending little published pieces from the Longhouse imprint, all manner of shape, color, and size. He and Susan compile these items at home. Inexpensive production, truly elegant, hand-made with a carpenter’s eye for craft. Like all good craft, the material carefully selected is minimal; handiwork is what’s foremost.

The pieces came by postal mail, for the spirit—from the center of what I began to regard as an elaborate & well developed mandala. Their ethos was one I knew, articulated a little differently, from living in Berkeley. It shared characteristics with the way Friedlander and I used gear at the local copy center for House of “K;” with my earlier days working at the happily drug-dazed anarchist collective, Bookpeople; with the thrill that what mattered happened in the smallest presses away from the colonizing gaze of universities. A few hidden places did this “real work,” to use Gary Snyder’s phrase. Yet Longhouse struck me as unique.

What surprised me was the variety of publications Longhouse produced, and what a range of poets. Not only did Bob seem to read everything, he seemed in touch with so many different sorts of poets, North American, and overseas. I still know no one else with that bio-spirit reach across geographies & through generations. To paraphrase Mark Twain, nothing is more fatal to sectarianism than wide reading.

Longhouse has published American poetry alongside translations from Persian, Khmer, Japanese, Portuguese, Arabic, Korean, Italian, & Chinese. It finds writers in Germany, India, Italy, Scotland, and Japan. Nature poets, tough-minded language poets, New American poets, troubadours, translators, science fiction feminists, concrete poets, romantics, hermits, herbalists, potter women, & dandies. I’d seen offerings like this in Jerry Rothenberg’s collections of the seventies, such as America: A Prophecy: gigantic global markets under one wide pagoda roof. Here were Bob and Susan doing it bit by bit, one chaplet, bus ticket, flyer, postcard, or packet at a time.

*

Before I moved to Colorado from the East Bay I would visit friends—poets, botanists, Zen people, carpenters, teachers—on the then-somewhat-remote San Juan Ridge, up from Grass Valley in the Sierra Nevada foothills. What drew me was how capable the Ridge homesteaders were with tools, something I rarely saw among scholarly poet-folk in the cities. Ridge poets had built their houses themselves, tucking them into the contours of the land, using trees felled on the building site, local river stones, and fashioning decor of antler, bone, herbs, clay, and wildflowers. The residents hammered nails, lay sheet rock, plumbed & painted. When you stepped inside, self-built bookshelves rose to the ceilings. These people, quietly removed from cities, had a dual ease of manner. They used books; they used tools.

That’s the “feel” I got the moment I walked into Bob and Susan’s place on Green River. I was east to visit my brother up Route 91 from Brattleboro, borrowed his car, and with Althea my daughter in tow, drove to the Arnolds. I could see the back country character of the intellectual when we pulled in alongside the old farmhouse. The massive 20th century split, of intellect away from hand-skill, hadn’t gotten here.

We got to know each other standing around the kitchen with its low ceiling—the house dates from the late 1700s and has that tighter use of space than does the intermountain West, where I live. We looked through tiny kitchen windows at New England hardwood forests, drinking tea, talking over all the things you don’t bother to put in letters. Susan had baked a pie with local fruit. Carson couldn’t wait to show us his drum set. Blond hair flying he bolted up a little staircase. Althea and I gave chase. On the landing—like sorcery—Althea whipped to a stop. Like Glinda had arrested her with one spangled sweep of the wand. A low bookshelf was staring at us. Every title in it an OZ book, the old ones, with that symbol of American mythos—

Neither of us had seen such a collection of OZiana.

*

All Longhouse publications are inventive in different ways. I like best the bright-packeted foldouts, what I took to calling the “chaplet,” “a little item of trade.” These are folded covers of cardstock or construction paper, with a paper wrap-around label, noting title and author, that serves as a band to hold the cover tight. Slide the band off, open the colorful wrap, and one or two narrow sheets unfold. Poems, translations, or in a few cases something like a small essay, scroll down in folded panels. JB Bryan of La Alameda press calls them “origami for the mind.”

The chaplets are unique. They take stalwart labor to prepare, especially when technology changes and Bob and Susan need to figure out how to institute a new design. Such as when printers with affordable colored ink came in. They then cut, fold, & paste together each chaplet. They place some in the mail, along with letters to correspondents; hold some back to sell through their website; surely they archive a few for readers of the centuries to come.

Longhouse makes other items too: postcards, bookmarks, folded mailing sheets, a blizzard of happy origami. Most get built to fit an ordinary envelope, and you can sail them out with a single first-class stamp. Then once or twice a year they produce a full-length book—by Bob himself, or by one of the members of their poetry clan. I see from the Longhouse bibliography that Bob and Susan produced twenty-three items in 2004, twenty-six the following year, and in 2006 thirty. That’s a clip of more than one publication every two weeks!

Meanwhile Bob writes books of his own, poem books, or memoirs of stonework, of his love for Susan, of family life, train travel, friends. Two recent books of his own turn out to be light on words. They hold drawings, with quick-sketched thought inked on the page. I particularly slap my thigh at Poets Who Sleep. It’s 600 pages—each page a rough-hewn ink-likeness of the face of a poet or artist, graffiti’d with words Bob finds to capture the person’s character. The word-characterizations are quick, accurate, impressionist, like the facial caricatures. On my door at work I posted the page he did of me. Over my growling comically severe unshaven face, SANSKRIT in big red letters. Three yellow stars drop through space. Below the Fudo-like scowl, my name in green. Then small black capitals,

POET, TRANSLATOR, INSTRUCTOR, ECO-WARRIOR WAS BORN IN 1953 IN MASSACHUSETTS BUT HAS SPENT MOST OF HIS ADULT LIFE IN WEST COAST LORE, WORK & LOVES

*

I’ve visited Bob & Susan half a dozen times out at Green River, maybe twice that. They don’t get a lot of visitors to Longhouse, (I was going to say “since they tore the jukebox out,” but really it’s now that Jim Koller is dead). They treat guests good, offer homemade snacks & tea. But I suspect they go back to what they love best: one another, their work, the books, the lives thronged with friends who live far-off.

What do you do with lots of solitude? Bob keeps adding to the whimsical and solid cottages that contour the clearing around the main house. Beyond the perimeter, it’s forest, with the road and river below. Inside the yard it’s a faery town Yeats would sing: of stone & timber made. Huts & cottages, odd intimate nooks, surprise vistas, shadowy windows, little flower beds, funny staircases, foundations that will last centuries. There’s a new blue-roof open woodshed for the cordwood overflow from the traditional shed, which has been attached to the house Vermont style since the original builder framed it.

The other cottages are fitted, ornamented, sometimes stuffed to the eaves with books. (Longhouse once held a drop-in bookstore, even had a shingle hung by the dirt road; now it’s mostly online.)

The cottages are history vaults and library as much as warehouse. Cartons of Cid Corman material (Origin Press); the papers of poet Janine Pommy Vega; Lorine Niedecker artifacts; hundreds of little magazines from the fifties forward; I don’t know what’s in all those cottages. One built more recently has a magic hobbit loft of childrens’ books for the grandkids. Bob shows me around. I stare at bookspines and try to foresee how Fate unfolds. We wind on foot through hardwoods along the centuries-old logging road, to the hilltop. There under a stone-cairn sit some of Cid Corman’s ashes. And you can see—Bob points through the trees—south into Massachusetts.

Since Bob is always restructuring his buildings—or adding new ones—you need to visit every few years just to keep up. Walkways, staircases, decks, windows, rock walls, inventively located foundations (one on top a huge shelf of old dark New England bedrock), root cellars, bookshelves, keep emerging. I study the handiwork and wonder what will happen here in the next century.

The visits are infrequent and brief though. Our friendship has been carried by letter. Poets, friends, children, music, politics, sports, travel: swapping the news by mail. The two of us are men of letters. We grew up in a paper era, before email or cheap phone service. It began with typewriter ribbons & postage stamps, handwritten postcards, priority labels on new books. It shifted to laser printers, but always handwritten addresses. The pokey old post office has proved a trustworthy pony indeed. The pace of letter writing stays when you have developed the habit.

You could say letter writing is the habit that made us friends. Letter writing is the habitat that holds us. Thirty or forty years a pretty stable ecosystem. It has provided shelter, food, friendship, a lot of poetry, and that thing you can’t quantify: love. As well as gossip, opinion, off-hand remarks, anger at how things go down in this avaricious world, rage towards politicians & culture mavens, stray comments on books, art, landscapes, or back roads we find serviceable. The whole stew from which “all poetry flows... and dreadfully much else.”

Andrew Schelling

Sugarloaf, Colorado

May 2022

I Cut A Massive Maple Tree Down

I cut a massive maple tree down

Long time ago

I sculptured the tree stump into a chair

I sat up there

I also sat up there with my baby son

I sat up there with my true love

I later saw my love sitting up there alone in the sun

She had a checkered red and black wool shirt

Thrown with the blondest hair

Then a chipmunk sat there for longer than you would think

And today I tore the carbonized tissue stump apart with my hands

All of it, very easily

And my son visited us with his wife for part of the afternoon

And in a week she was gone

How Wars Begin

What he

Calls a

Log

I call

A

Tree

Self-Employed

Take two squared stones and

Drop them almost side by side

Lift the thinner slab of rock and

Bust your guts setting it on top

Now you got reason to sit down

Show Me

I don’t walk this

Early morning, frost

On the mowing, but you do —

And when you return

I’m sitting by the

Cookstove warm as you bend

To shiver my neck a kiss —

Show me what I missed

The Woodcutter Talks

Long before the great ships at sea

There were the deep inland forests

I stand in one today knee-deep in snow

10 degrees with a wind

My saw shut down

Oil freeze to bar and gloves

Listening awhile to the ships at sea

The long groaning waves

High high

Above me

Duo

The same bird every night

In the same tree singing

The same song that does

The same very songful

Thing inside of me

No Tool Or Rope Or Pail

It hardly mattered what time of year

We passed by their farmhouse

They never waved,

This old farm couple

Usually bent over in the vegetable garden

Or walking the muddy dooryard

Between house and red-weathered barn.

They would look up, see who was passing,

Then look back down, ignorant to the event.

We would always wave nonetheless,

Before you dropped me off at work

Further up on the hill,

Toolbox rattling in the backseat,

And then again on the way home

Later in the day, the pale sunlight

High up in their pasture,

Our arms out the window

Cooling ourselves.

And it was that one midsummer evening

We drove past and caught them sitting

Together on the front porch

At ease, chores done,

The tangle of cats and kittens

Cleaning themselves of fresh spilled milk

On the barn door ramp,

We drove by and they looked up —

The first time I’ve ever seen their

Hands free of any work,

No tool or rope or pail —

And they waved.

Love And Landscape

Don’t ask us how we crossed the saltwater marsh

Grasses were high and easy under foot

The last stream was spanned by a driftwood plank

Thrown carefully into the muck

I didn’t sink and you didn’t sink

And when we came to ocean

Skittering of sandpipers

You held your dress and walked into the spray

It must have been also the sudden daylight that I loved

Walk To the Barn

All of life, even the mountains

Around him are changing

Yet he walks twice each day

To the barn up the wide gravel drive

No more cattle inside

His slow and steady pace

Pays respect to the surrounding pasture

The ring of woodland and evening birds

What once made him prosperous

Is now gone, except for what he loves —

His wife, old dog, farm buildings and land —

He leans open the heavy sliding barn door

Steps out of view

Is It

river

flowing

beneath

the stars

or stars

flowing

over the

river

———————————

Bob Arnold