OCCUPY ~ Rebecca Solnit

Rebecca Solnit

Occupy Heads into the Spring

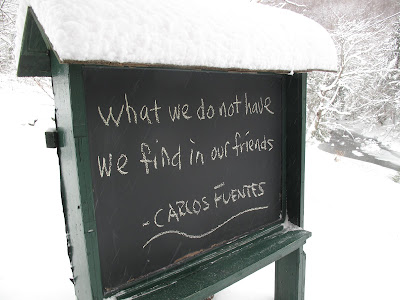

By Rebecca SolnitWhen you fall in love, it’s all about what you have in common, and you can hardly imagine that there are differences, let alone that you will quarrel over them, or weep about them, or be torn apart by them -- or if all goes well, struggle, learn, and bond more strongly because of, rather than despite, them. The Occupy movement had its glorious honeymoon when old and young, liberal and radical, comfortable and desperate, homeless and tenured all found that what they had in common was so compelling the differences hardly seemed to matter.

Until they did.

Revolutions are always like this: at first all men are brothers and anything is possible, and then, if you’re lucky, the romance of that heady moment ripens into a relationship, instead of a breakup, an abusive marriage, or a murder-suicide. Occupy had its golden age, when those who never before imagined living side-by-side with homeless people found themselves in adjoining tents in public squares.

All sorts of other equalizing forces were present, not least the police brutality that battered the privileged the way that inner-city kids are used to being battered all the time. Part of what we had in common was what we were against: the current economy and the principle of insatiable greed that made it run, as well as the emotional and economic privatization that accompanied it.

This is a system that damages people, and its devastation was on display as never before in the early months of Occupy and related phenomena like the “We are the 99%” website. When it was people facing foreclosure, or who’d lost their jobs, or were thrashing around under avalanches of college or medical debt, they weren’t hard to accept as us, and not them.

And then came the people who’d been damaged far more, the psychologically fragile, the marginal, and the homeless -- some of them endlessly needy and with a huge capacity for disruption. People who had come to fight the power found themselves staying on to figure out available mental-health resources, while others who had wanted to experience a democratic society on a grand scale found themselves trying to solve sanitation problems.

And then there was the violence.

The Faces of Violence

The most important direct violence Occupy faced was, of course, from the state, in the form of the police using maximum sub-lethal force on sleepers in tents, mothers with children, unarmed pedestrians, young women already penned up, unresisting seated students, poets, professors, pregnant women, wheelchair-bound occupiers, and octogenarians. It has been a sustained campaign of police brutality from Wall Street to Washington State the likes of which we haven’t seen in 40 years.

On the part of activists, there were also a few notable incidents of violence in the hundreds of camps, especially violence against women. The mainstream media seemed to think this damned the Occupy movement, though it made the camps, at worst, a whole lot like the rest of the planet, which, in case you hadn’t noticed, seethes with violence against women. But these were isolated incidents.

That old line of songster Woody Guthrie is always handy in situations like this: “Some will rob you with a six-gun, some with a fountain pen.” The police have been going after occupiers with projectile weapons, clubs, and tear gas, sending some of them to the hospital and leaving more than a few others traumatized and fearful. That’s the six-gun here.

But it all began with the fountain pens, slashing through peoples’ lives, through national and international economies, through the global markets. These were wielded by the banksters, the “vampire squid,” the deregulators in D.C., the men -- and with the rarest of exceptions they were men -- who stole the world.

That’s what Occupy came together to oppose, the grandest violence by scale, the least obvious by impact. No one on Wall Street ever had to get his suit besmirched by carrying out a foreclosure eviction himself. Cities provided that service for free to the banks (thereby further impoverishing themselves as they created new paupers out of old taxpayers). And the police clubbed their opponents for them, over and over, everywhere across the United States.

The grand thieves invented ever more ingenious methods, including those sliced and diced derivatives, to crush the hopes and livelihoods of the many. This is the terrible violence that Occupy was formed to oppose. Don’t ever lose sight of that.

Oakland’s Beautiful Nonviolence

Now that we’re done remembering the major violence, let’s talk about Occupy Oakland. A great deal of fuss has been made about two incidents in which mostly young people affiliated with Occupy Oakland damaged some property and raised some hell.

The mainstream media and some faraway pundits weighed in on those Bay Area incidents as though they determined the meaning and future of the transnational Occupy phenomenon. Perhaps some of them even hoped, consciously or otherwise, that harped on enough these might divide or destroy the movement. So it’s important to recall that the initial impact of Occupy Oakland was the very opposite of violent, stunningly so, in ways that were intentionally suppressed.

Occupy Oakland began in early October as a vibrant, multiracial gathering. A camp was built at Oscar Grant/Frank Ogawa Plaza, and thousands received much-needed meals and healthcare for free from well-organized volunteers. Sometimes called the Oakland Commune, it was consciously descended from some of the finer aspects of an earlier movement born in Oakland, the Black Panthers, whose free breakfast programs should perhaps be as well-remembered and more admired than their macho posturing.

A compelling and generous-spirited General Assembly took place nightly and then biweekly in which the most important things on Earth were discussed by wildly different participants. Once, for instance, I was in a breakout discussion group that included Native American, white, Latino, and able-bodied and disabled Occupiers, and in which I was likely the eldest participant; another time, a bunch of peacenik grandmothers dominated my group.

This country is segregated in so many terrible ways -- and then it wasn’t for those glorious weeks when civil society awoke and fell in love with itself. Everyone showed up; everyone talked to everyone else; and in little tastes, in fleeting moments, the old divides no longer divided us and we felt like we could imagine ourselves as one society. This was the dream of the promised land -- this land, that is, without its bitter divides. Honey never tasted sweeter, and power never felt better.

Now here’s something astonishing. While the camp was in existence, crime went down 19% in Oakland, a statistic the city was careful to conceal. "It may be counter to our statement that the Occupy movement is negatively impacting crime in Oakland," the police chief wrote to the mayor in an email that local news station KTVU later obtained and released to little fanfare. Pay attention: Occupy was so powerful a force for nonviolence that it was already solving Oakland’s chronic crime and violence problems just by giving people hope and meals and solidarity and conversation.

The police attacking the camp knew what the rest of us didn’t: Occupy was abating crime, including violent crime, in this gritty, crime-ridden city. “You gotta give them hope, “ said an elected official across the bay once upon a time -- a city supervisor named Harvey Milk. Occupy was hope we gave ourselves, the dream come true. The city did its best to take the hope away violently at 5 a.m. on October 25th. The sleepers were assaulted; their belongings confiscated and trashed. Then, Occupy Oakland rose again. Many thousands of nonviolent marchers shut down the Port of Oakland in a stunning display of popular power on November 2nd.

That night, some kids did the smashy-smashy stuff that everyone gets really excited about. (They even spray-painted “smashy” on a Rite Aid drugstore in giant letters.) When we talk about people who spray-paint and break windows and start bonfires in the street and shove people and scream and run around, making a demonstration into something way too much like the punk rock shows of my youth, let’s keep one thing in mind: they didn’t send anyone to the hospital, drive any seniors from their homes, spread despair and debt among the young, snatch food and medicine from the desperate, or destroy the global economy.

That said, they are still a problem. They are the bait the police take and the media go to town with. They create a situation a whole lot of us don’t like and that drives away many who might otherwise participate or sympathize. They are, that is, incredibly bad for a movement, and represent a form of segregation by intimidation.

But don’t confuse the pro-vandalism Occupiers with the vampire squid or the up-armored robocops who have gone after us almost everywhere. Though their means are deeply flawed, their ends are not so different than yours. There’s no question that they should improve their tactics or maybe just act tactically, let alone strategically, and there’s no question that a lot of other people should stop being so apocalyptic about it.

Those who advocate for nonviolence at Occupy should remember that nonviolence is at best a great spirit of love and generosity, not a prissy enforcement squad. After all, the Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr., who gets invoked all the time when such issues come up, didn’t go around saying grumpy things about Malcolm X and the Black Panthers.

Violence Against the Truth

Of course, a lot of people responding to these incidents in Oakland are actually responding to fictional versions of them. In such cases, you could even say that some journalists were doing violence against the truth of what happened in Oakland on November 2nd and January 28th.

The San Francisco Chronicle, for example, reported on the day’s events this way:

"Among the most violent incidents that occurred Saturday night was in front of the YMCA at 23rd Street and Broadway. Police corralled protesters in front of the building and several dozen protesters stormed into the Y, apparently to escape from the police, city officials and protesters said. Protesters damaged a door and a few fixtures, and frightened those inside the gym working out, said Robert Wilkins, president of the YMCA of the East Bay.”

Wilkins was apparently not in the building, and first-person testimony recounts that a YMCA staff member welcomed the surrounded and battered protesters, and once inside, some were so terrified they pretended to work out on exercise machines to blend in.

I wrote this to the journalists who described the incident so peculiarly: “What was violent about [activists] fleeing police engaging in wholesale arrests and aggressive behavior? Even the YMCA official who complains about it adds, ‘The damage appears pretty minimal.’ And you call it violence? That's sloppy.”

The reporter who responded apologized for what she called her “poor word choice” and said the phrase was meant to convey police violence as well.

When the police are violent against activists, journalists tend to frame it as though there were violence in some vaguely unascribable sense that implicates the clobbered as well as the clobberers. In, for example, the build-up to the 2004 Republican National Convention in New York City, the mainstream media kept portraying the right of the people peaceably to assemble as tantamount to terrorism and describing all the terrible things that the government or the media themselves speculated we might want to do (but never did).

Some of this was based on the fiction of tremendous activist violence in Seattle in 1999 that the New York Times in particular devoted itself to promulgating. That the police smashed up nonviolent demonstrators and constitutional rights pretty badly in both Seattle and New York didn’t excite them nearly as much. Don’t forget that before the obsession with violence arose, the smearing of Occupy was focused on the idea that people weren’t washing very much, and before that the framework for marginalization was that Occupy had “no demands.” There’s always something.

Keep in mind as well that Oakland’s police department is on the brink of federal receivership for not having made real amends for old and well-documented problems of violence, corruption, and mismanagement, and that it was the police department, not the Occupy Oakland demonstrators, which used tear gas, clubs, smoke grenades, and rubber bullets on January 28th. It’s true that a small group vandalized City Hall after the considerable police violence, but that’s hardly what the plans were at the outset of the day.

The action on January 28th that resulted in 400 arrests and a media conflagration was called Move-In Day. There was a handmade patchwork banner that proclaimed “Another Oakland Is Possible” and a children’s contingent with pennants, balloons, and strollers. Occupy Oakland was seeking to take over an abandoned building so that it could reestablish the community, the food programs, and the medical clinic it had set up last fall. It may not have been well planned or well executed, but it was idealistic.

Despite this, many people who had no firsthand contact with Occupy Oakland inveighed against it or even against the whole Occupy movement. If only that intensity of fury were to be directed at the root cause of it all, the colossal economic violence that surrounds us.

All of which is to say, for anyone who hadn’t noticed, that the honeymoon is over.

Now for the Real Work

The honeymoon is, of course, the period when you’re so in love you don’t notice differences that will eventually have to be worked out one way or another. Most relationships begin as though you were coasting downhill. Then come the flatlands, followed by the hills where you’re going to have to pedal hard, if you don’t just abandon the bike.

Occupy might just be the name we’ve put on a great groundswell of popular outrage and a rebirth of civil society too deep, too broad, to be a movement. A movement is an ocean wave: this is the whole tide turning from Cairo to Moscow to Athens to Santiago to Chicago. Nevertheless, the American swell in this tide involves a delicate alliance between liberals and radicals, people who want to reform the government and campaign for particular gains, and people who wish the government didn’t exist and mostly want to work outside the system. If the radicals should frighten the liberals as little as possible, surely the liberals have an equal obligation to get fiercer and more willing to confront -- and to remember that nonviolence, even in its purest form, is not the same as being nice.

Surely the only possible answer to the tired question of where Occupy should go from here (as though a few public figures got to decide) is: everywhere. I keep being asked what Occupy should do next, but it’s already doing it. It is everywhere.

In many cities, outside the limelight, people are still occupying public space in tents and holding General Assemblies. February 20th, for instance, was a national day of Occupy solidarity with prisoners; Occupiers are organizing on many fronts and planning for May Day, and a great many foreclosure defenses from Nashville to San Francisco have kept people in their homes and made banks renegotiate. Campus activism is reinvigorated, and creative and fierce discussions about college costs and student debt are underway, as is a deeper conversation about economics and ethics that rejects conventional wisdom about what is fair and possible.

Occupy is one catalyst or facet of the populist will you can see in a host of recent victories. The campaign against corporate personhood seems to be gaining momentum. A popular environmental campaign made President Obama reject the Keystone XL tar sands pipeline from Canada, despite immense Republican and corporate pressure. In response to widespread outrage, the Susan B. Komen Foundation reversed its decision to defund cancer detection at Planned Parenthood. Online campaigns have forced Apple to address its hideous labor issues, and the ever-heroic Coalition of Immokalee Workers at last brought Trader Joes into line with its fair wages for farmworkers campaign.

These genuine gains come thanks to relatively modest exercises of popular power. They should act as reminders that we do have power and that its exercise can be popular. Some of last fall’s exhilarating conversations have faltered, but the great conversation that is civil society awake and arisen hasn’t stopped.

What happens now depends on vigorous participation, including yours, in thinking aloud together about who we are, what we want, and how we get there, and then acting upon it. Go occupy the possibilities and don’t stop pedaling. And remember, it started with mad, passionate love.

TomDispatch regular Rebecca Solnit is the author of 13 (or so) books, including A Paradise Built in Hell: The Extraordinary Communities that Arise in Disaster and Hope in the Dark. She lives in and occupies from San Francisco.

Copyright 2012 Rebecca SolnitTomdispatch.com21 February 2012thank you to Geoffrey Gardner